Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini, pioneer of SLAC’s X-ray laser

Leading researchers met at SLAC on Pellegrini’s 90th birthday to honor his ongoing scientific legacy and to explore the future of X-ray free-electron laser science.

By Manuel Gnida

Linac Coherent Light Source

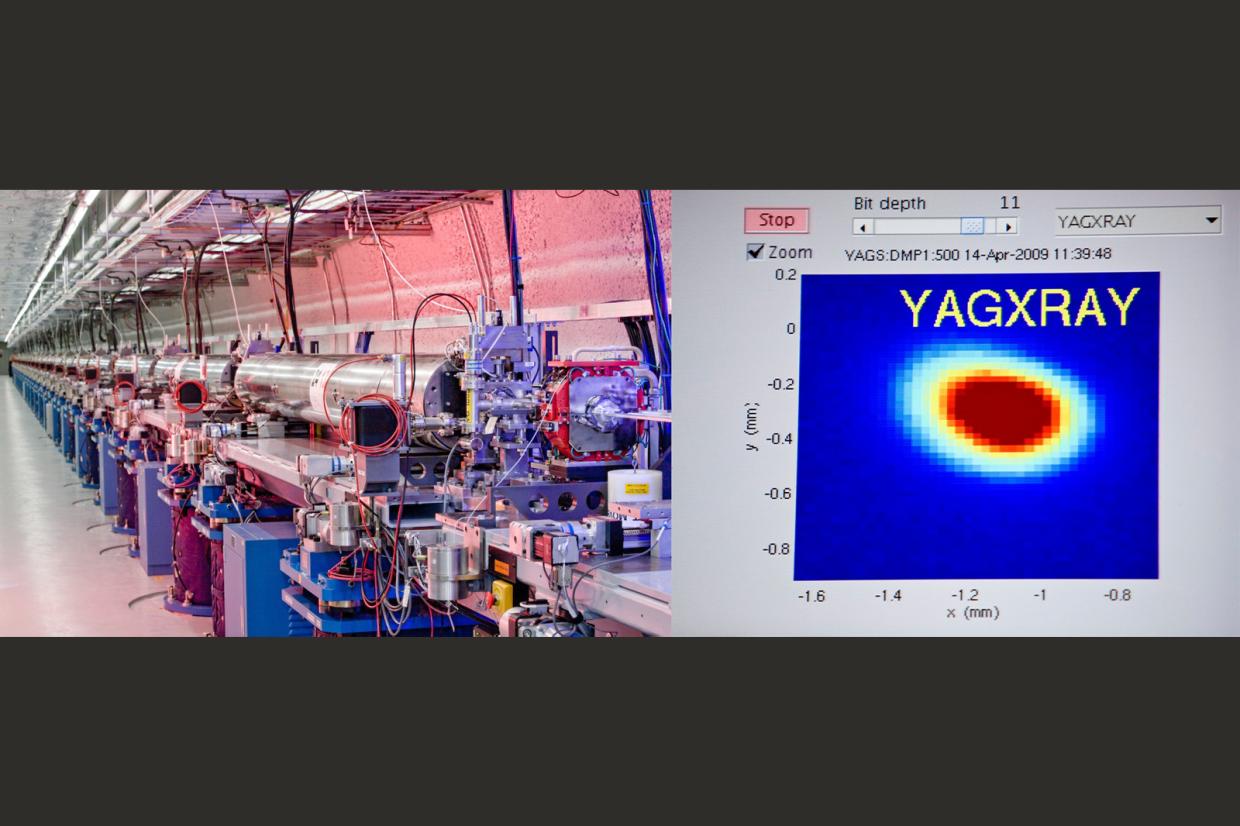

The Linac Coherent Light Source at SLAC, the world’s first hard X-ray free-electron laser, takes X-ray snapshots of atoms and molecules at work, revealing fundamental processes in materials, technology and living things.

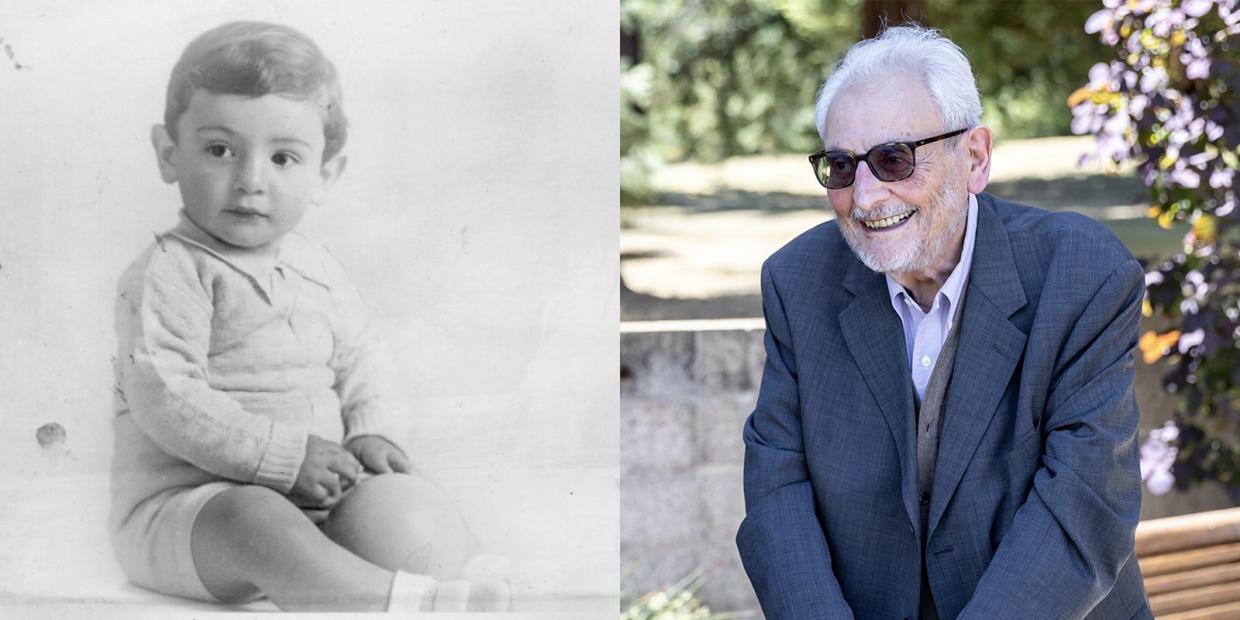

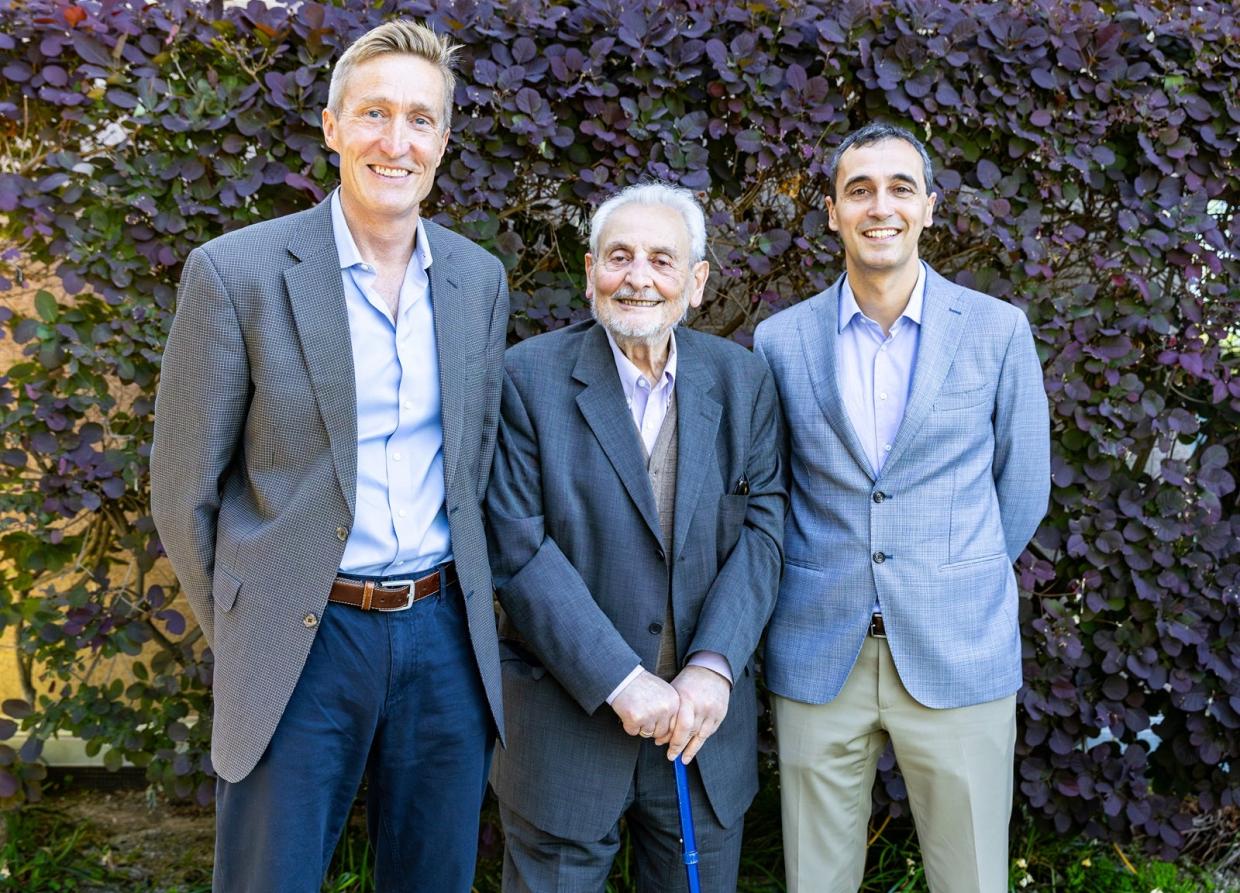

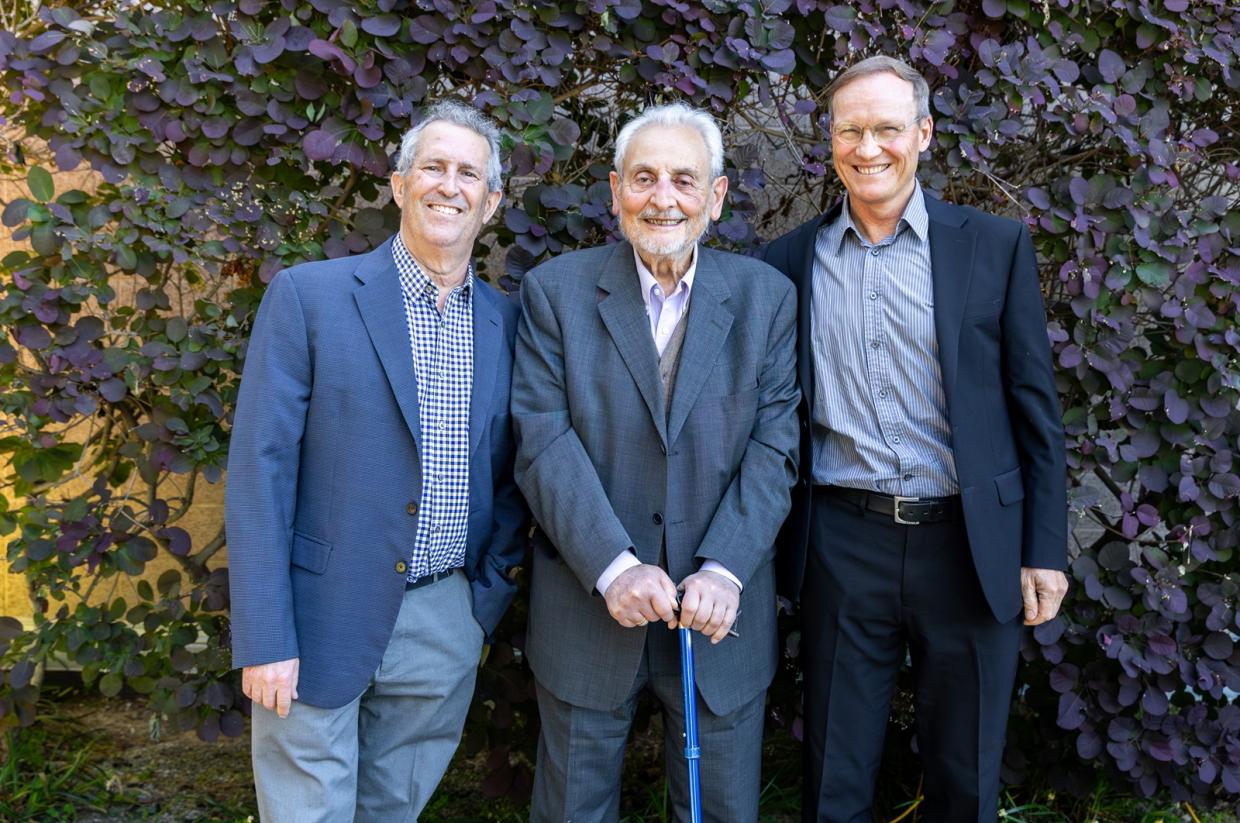

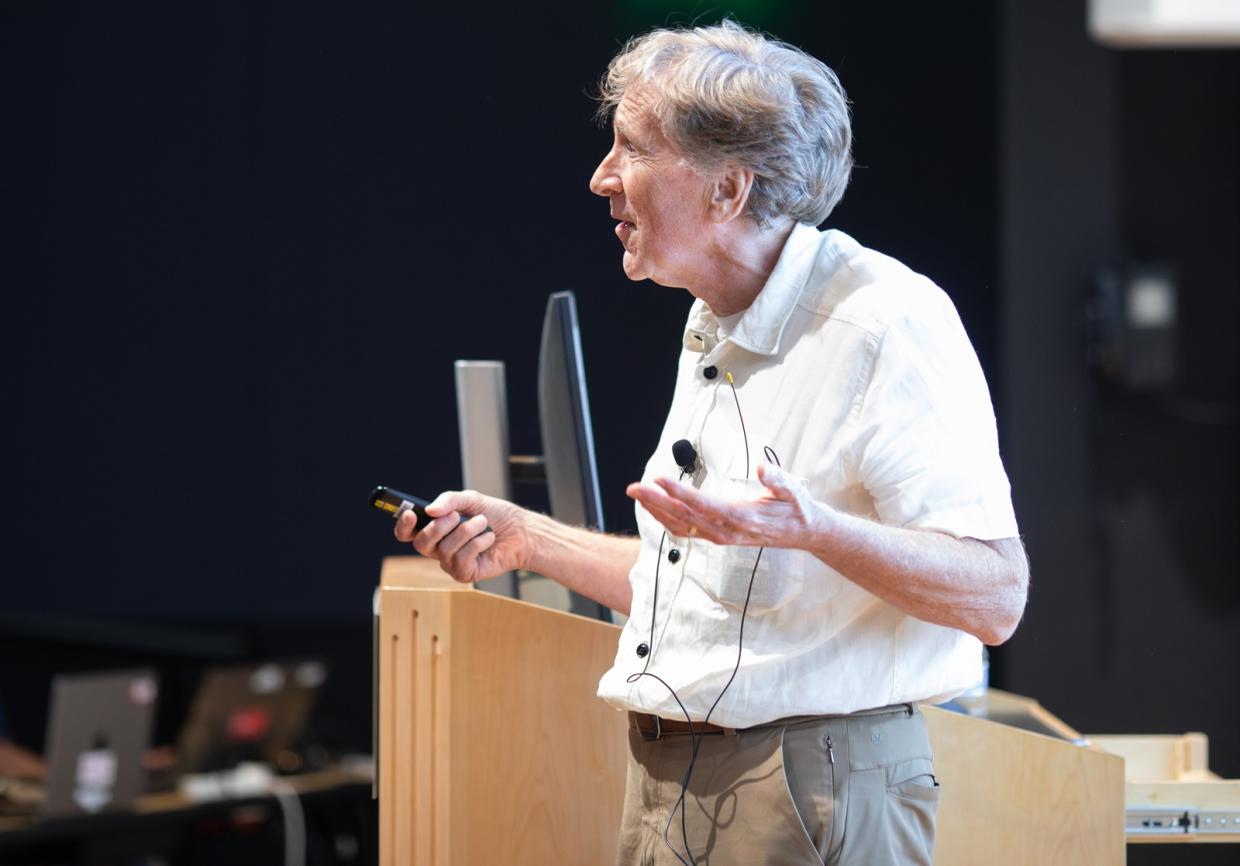

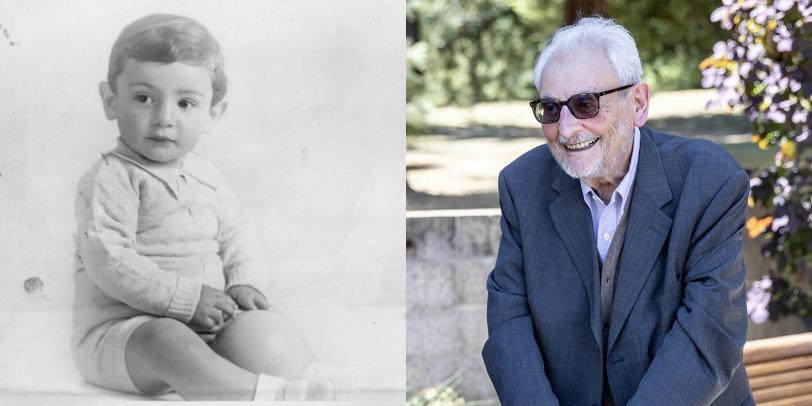

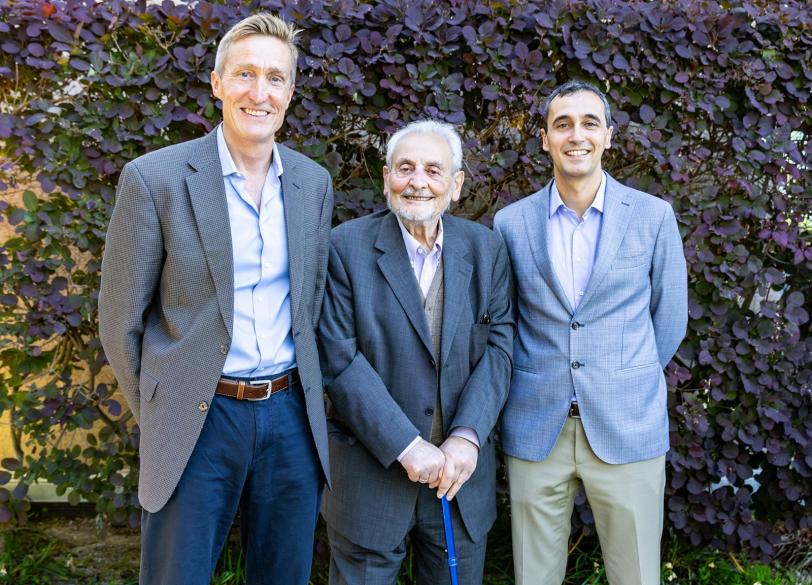

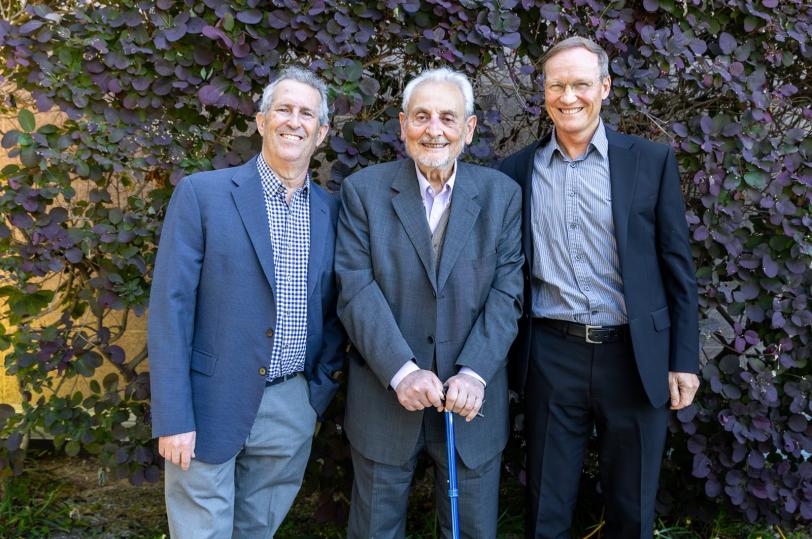

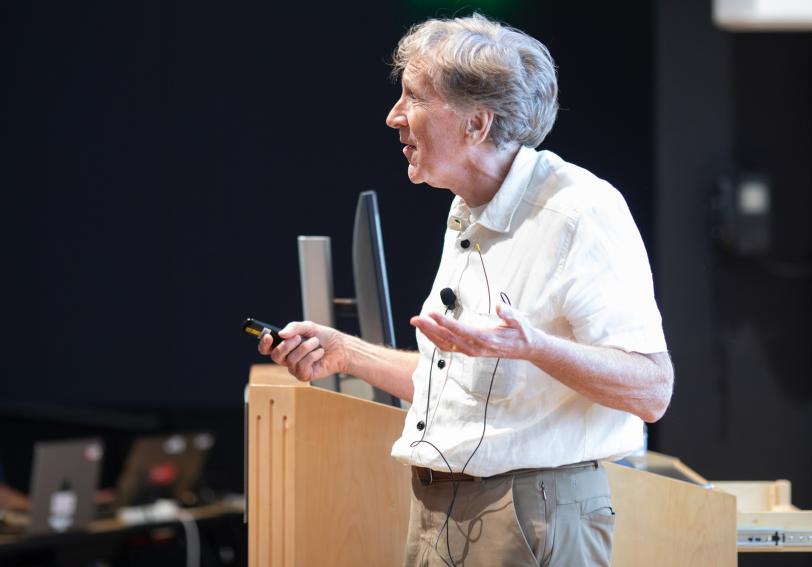

Ask anyone about Claudio Pellegrini – distinguished professor emeritus of physics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and adjunct professor of photon science at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory – and they are quick to share their heartfelt admiration. They describe a gentle giant, widely regarded for his influential work and noble character; a charismatic and curious leader who ushered in a whole new way of doing science; a mentor, friend and someone who has become a father or grandfather figure to many in the accelerator and free-electron laser science community.

On May 9, 2025, on Pellegrini’s 90th birthday, SLAC hosted a special symposium to honor his ongoing scientific legacy.

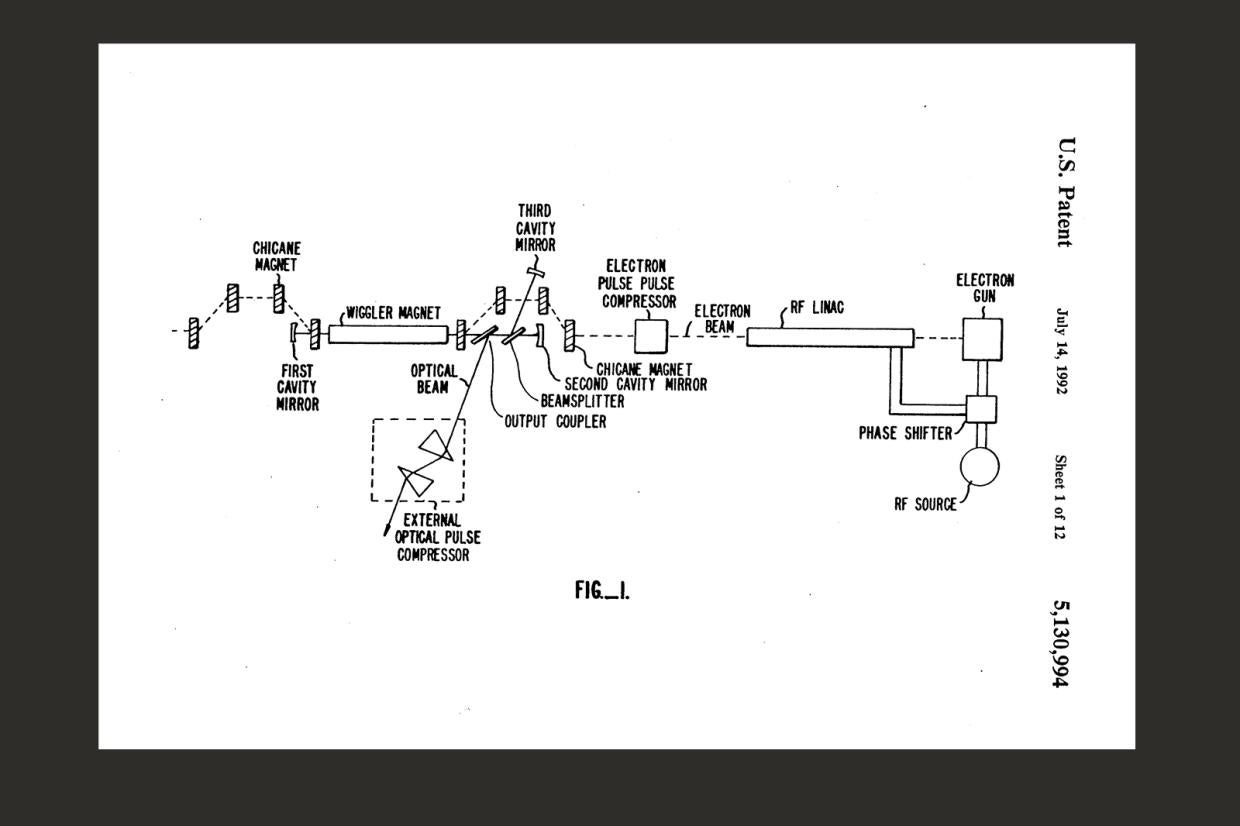

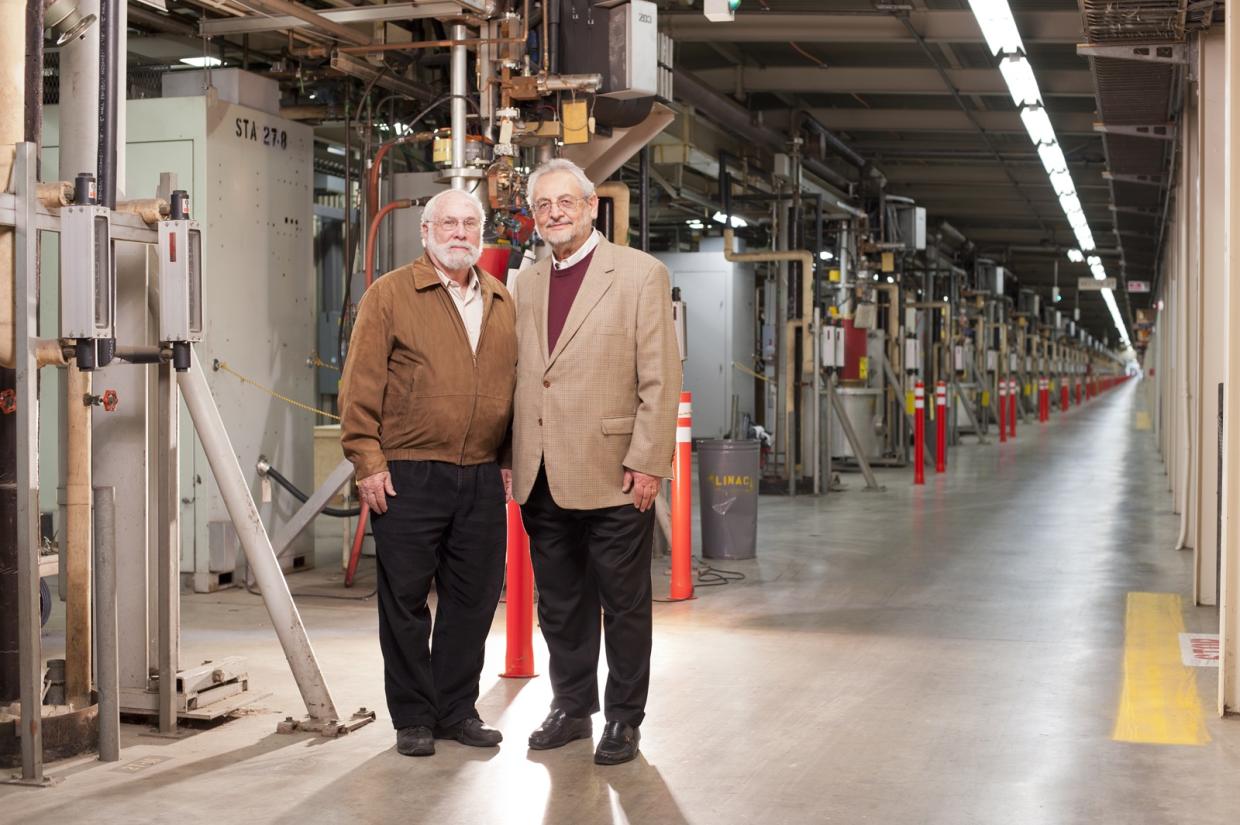

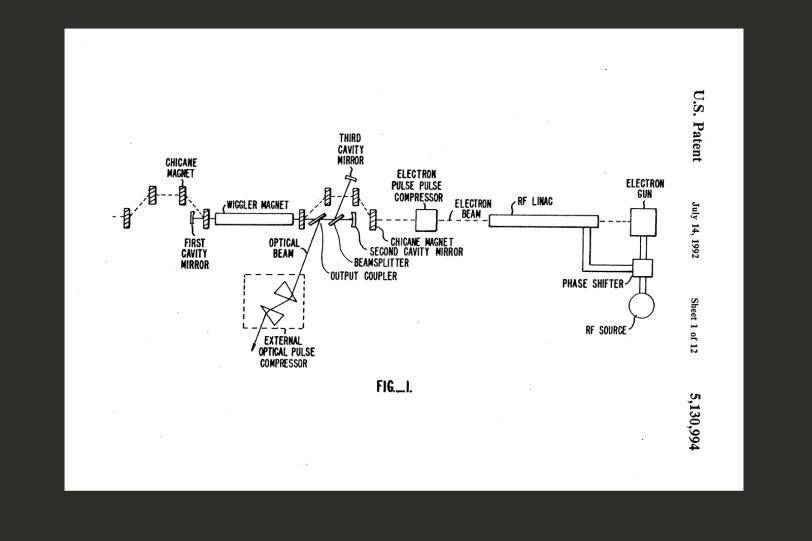

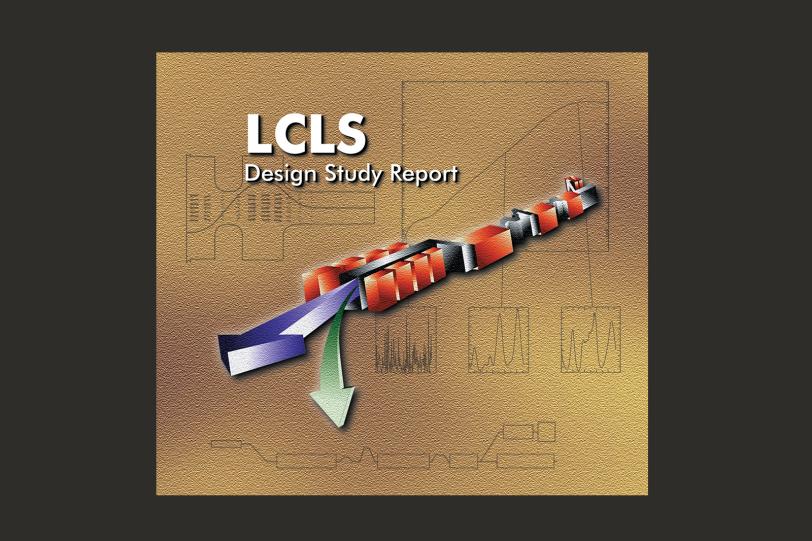

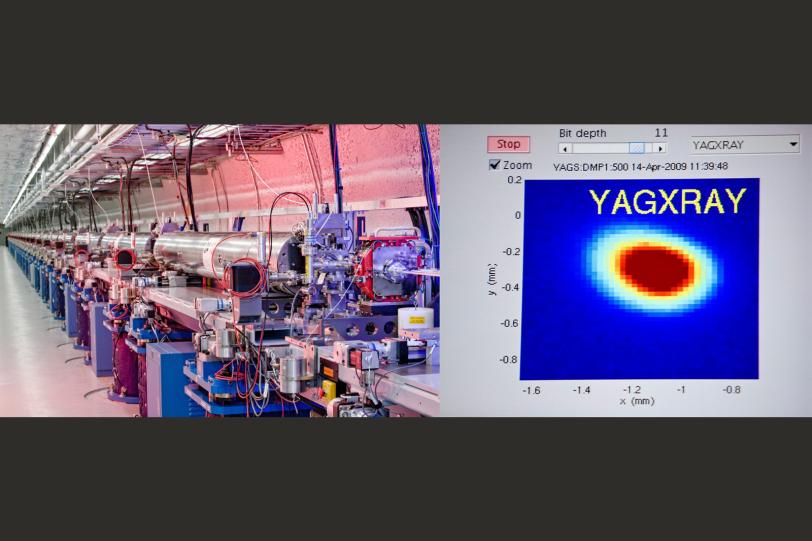

Among Pellegrini’s many accomplishments, one moment in time stands out. At a workshop on fourth generation light sources in 1992, he proposed to use SLAC’s historic linear accelerator to build an X-ray free-electron laser. That visionary idea became reality in 2009 when SLAC turned on its Linac Coherent Lightsource (LCLS), the world’s first free-electron laser producing “hard,” or very high-energy, X-rays.

Click through the photo carousel to learn more about the development of the LCLS idea, Pellegrini’s contributions, and what his colleagues had to say about his legacy at the May 9 symposium.

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

Symposium celebrates Claudio Pellegrini

When LCLS came online, it was a revolutionary new facility. With its unprecedented flashes of X-ray light that each only last a few millionths of a billionth of a second and are a billion times brighter than those produced by any previous source, researchers could now do science they could only dream of before. For example, LCLS allowed them to take snapshots of atoms and molecules at work and string them together in molecular movies that reveal chemical reactions and other fundamental ultrafast processes in real time in materials, technology and living things.

While the goal behind Pellegrini’s proposal was clear from the beginning, it was also apparent that turning it into a working machine would be an extraordinary technological challenge. “It didn’t seem to be impossible, but we certainly needed to do our homework,” Pellegrini remembers. “It took a place like SLAC with its technical capabilities and the collective effort of many talented people in many places to make it happen.”

Since 2009, similar light sources have been developed around the world. Meanwhile, at SLAC, recent and future upgrades to LCLS ensure that its capabilities keep defining and pushing the frontiers of X-ray science and technology.

The symposium was organized by Uwe Bergmann, Martin L. Perl Endowed Professor of ultrafast X-ray science at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, together with LCLS’s Leilani Conradson, Samira Morton and Brandon Tan.

Further Information

- Symposium agenda and speaker list: Claudio90: Perspectives, Applications, and the Future of X-ray Lasers.

- SLAC Science Explained, XFELs: Spying on atoms and molecules

LCLS, SSRL and FACET-II are DOE Office of Science user facilities.

For questions or comments, contact SLAC Strategic Communications & External Affairs at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

About SLAC

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory explores how the universe works at the biggest, smallest and fastest scales and invents powerful tools used by researchers around the globe. As world leaders in ultrafast science and bold explorers of the physics of the universe, we forge new ground in understanding our origins and building a healthier and more sustainable future. Our discovery and innovation help develop new materials and chemical processes and open unprecedented views of the cosmos and life’s most delicate machinery. Building on more than 60 years of visionary research, we help shape the future by advancing areas such as quantum technology, scientific computing and the development of next-generation accelerators.

SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.